jan 11 | That's Shanghai

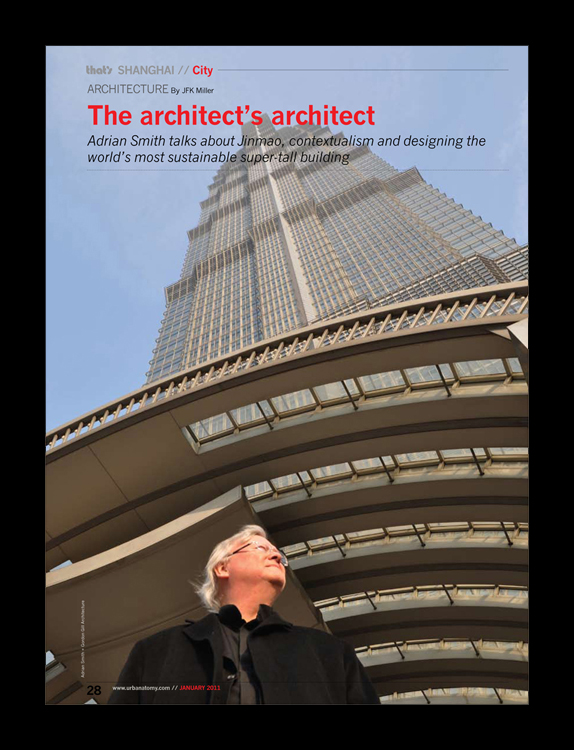

The architect's architect

by JFK Miller

Adrain Smith talks about Jinmao, contextualism and designing the world's most sustainable super-tall building.

The design of Shanghai’s iconic Jinmao Tower owes much to a fortune cookie in a Chicago Chinatown restaurant. In March 1993, the building’s architect, Adrian Smith, was visited by three envoys of the Chinese government – Mr. Zhang, Mr. Zu and Mr. Ruan – at the Chicago offices of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) where Smith was then a partner. They had come to introduce the project competition to SOM and solicit questions. Smith did have one: Why did the brief specify that the building must be 88 stories high? Could the site not have two buildings, perhaps a 50- story office and a 38-story hotel, instead of a tall mixed-use building? After all, said the American, it would be cheaper and would be constructed much quicker. The response was that the Jinmao had to be 88 stories because Deng Xiaoping was 88 when he stood on the site and announced it would be the new financial center of China. The time of Deng’s announcement – August 1988 – was also propitious. But it was a fortune cookie that would finally affirm the numerology. At lunch at the Blue Moon restaurant in Chinatown, Zhang opened the cookie handed to him and found the numbers 8, 15, 24, 32 and 40. An excited Zhang showed it to the group, which led Smith to observe that there were eight people around the table and that the date was March 24: 3 x 8 = 24.

“I knew then and there that I would design the building around the number eight,” he says.

The number eight would be one of many Chinese elements which Smith would incorporate into the design of the Jinmao, which formally opened on the auspicious date of August 28, 1998 (though the building would not be fully operational until the following year). The pagoda – one of the most important forms in indigenous Chinese architecture – provided part of the inspiration.

“My approach to architecture is that of a contextualist,” explains Smith. “The history and culture of the places I design buildings for are very important to me. I try to interpret and honor the societies that my buildings serve, and to forge a unique dialogue between culture and place. I want to foster a strong connection to the people who see and use my buildings.”

In the case of the Jinmao, Smith wanted to create an iconic landmark tower made specifically for China that could only be in China, hence the pagoda motif.

“I attempted to reinterpret it in a contemporary idiom and with contemporary technology, including digital design tools, and contemporary building materials, including aluminum and stainless steel cladding,” says Smith. “But I wasn’t trying to reproduce that form. No actual pagoda ever looked anything like the Jinmao.”

Many consider the Jinmao to be one of the 66-year-old architect’s best designs in a distinguished career which includes other landmark towers such as the Burj Khalifa – the tallest building in the world – and Trump Tower in Chicago. The soaring, much-photographed Grand Hyatt hotel atrium within the Jinmao has influenced other architects and been much copied.

“I think it’s fair to say that we did our homework,” says Smith. “We took care to understand as much as we could about Chinese history and culture, and in the end I think that depth of research and cultural respect was evident in the scheme. The client appreciated that, obviously.”

So too did the chairman of Guangdong Tobacco Corporation, who in 2005 invited Smith to design what may well become the crowning achievement of his 40-year career – the world’s first net-zero-energy skyscraper. That building, the Pearl River Tower in Guangzhou, will be completed this year.

“I believe it’s one of the most important projects I’ve been associated with in my career, in terms of demonstrating the crucial role that architectural form can play in making buildings – in particular super-tall structures – more sustainable. In that sense, the Pearl River Tower is a breakthrough of major importance and one that will have a considerable influence on the shaping of future towers.”

Smith began work on the building in 2005 with Gordon Gill, who is now his partner at Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, which they formed in 2006 after leaving SOM. To harvest wind power, for instance, they created an aerodynamic tower which would directly face the prevailing winds from the south and funnel them into building-integrated turbines at accelerated speeds. The tower’s shape also facilitates building integrated photovoltaics and improved structural performance, as the windturbine apertures act as pressure release valves. In addition, the design includes a double wall and a radiant chilled ceiling system with floor-fed fresh air supply, all of which work in concert to reduce energy costs while maximizing the comfort of the building’s occupants. Smith added the idea of shaping the ceiling slab to help reflect daylight coming into the building down onto the workspaces below. Fuel cell technology is also used. When completed, the Pearl River Tower will be the world’s most sustainable super-tall building.

Environmental factors are something which have guided Smith’s work since the late ’70s – well before the term ‘sustainability’ was in common use – and feed into his contextualist approach to architecture. In response to frequent power outages in Guatemala he designed three Banco de Occidente branches (completed in 1980) to operate without electricity if necessary, using courtyards and louvered skylights for daylighting and natural ventilation. In the desert climate of Bahrain, his United Gulf Bank (1986) features a wrapper wall with deeply recessed windows outfitted with heat-absorbing glass fins and light scoops. He later introduced the first double climate wall commercial structure in the United States, 601 Congress Street in Boston, which was completed in 2005. He considered a net-zero-energy building for a prominent site in downtown Chicago in the mid-90s, although the project did not go forward.

“When the Pearl River Tower project came along, I realized this was the opportunity we’d been waiting for,” he says.

“I believe it’s the first building of its kind to use the elements of natural forces in the environment to actually inform the shape of the tower. The shape is designed to harvest the wind and funnel it into the four openings in order to drive the wind turbines and generate power for the tower. We think this is a groundbreaking approach towards how wind and solar forces can be used to inform the shaping of buildings and cities in the future.”

It has been written that “the only person who can outbuild Adrian Smith is Adrian Smith.” And with the Burj Khalifa under this formidable architect’s belt, the statement is unquestionably accurate. At 828 meters it is the tallest man-made structure ever built and at least 100 meters higher than any existing building or building currently known to be in development.

The Chicago-based architect also has at least one work in progress that might even outperform the Pearl River Tower in terms of sustainability. Masdar Headquarters, now under construction outside Abu Dhabi and slated for completion in 2013, will be the world’s first large-scale ‘positive-energy’ building. In short, it will generate more energy than it consumes. Smith is also excited about Zifeng Tower in Nanjing, the world’s seventh-tallest building, completed in May 2010, on which he was Design Partner and Gordon Gill and Marshall Strabala – the architect of Shanghai Tower who we featured last issue – were studio heads working under his supervision while at SOM.